<H1>Heron the forgotten pioneer of U.S. soccer</H1>

By Frank Dell'Apa

Special to ESPN.com

If he were playing soccer today, Giles Heron might be preparing for Champions League games with Celtic FC. And, once his European career concluded, Heron would be recruited by the Chicago Fire to return to the city where his son was born and where his career was launched.

But when Heron became the first black player to perform for Celtic in 1951, there was no Champions League competition. Heron was accepted by Celtic supporters but, apparently, not the media. When Heron returned to the U.S., there was no demand he be included in World Cup preparations. As soccer's profile lowered, Heron also faded away.<DIV class=phinline>

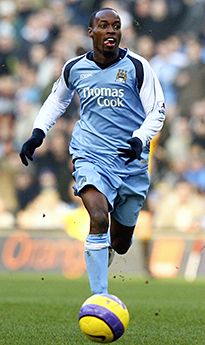

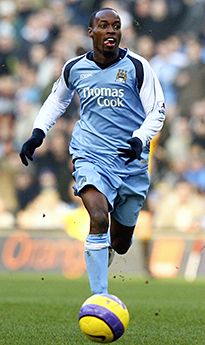

<DIV style="WIDTH: 205px"><DIV class=photocred2>Matthew Lewis/Getty Images</DIV><DIV class=photosubtext>DaMarcus Beasley is part of a modern generation of black players making their mark in U.S. soccer.</DIV></DIV></DIV>

Heron, Haiti-born Joe Gaetjens and Cuban Pito Villanon were among the top scorers in U.S. soccer in the 1940s and '50s. There is almost no written material available regarding the integration of black players into soccer in the U.S. during this time, but there must have been other black players involved in the many semi-professional leagues throughout the country.

In the early years of soccer, administrators and players of direct Northern European descent dominated the game in most countries, including the U.S. By the 1920s, many U.S.-born players were advancing into the professional ranks, Italian and Portuguese names beginning to appear on top teams in the late '20s. An African player, Egyptian inside forward Tewfik Abdallah, starred in the American Soccer League from 1924-28. But the professional game in the U.S. essentially mirrored the British for decades and players of sub-Saharan origins were mostly excluded.

The first native-born superstar soccer player in the U.S. was Adelino "Billy" Gonsalves, whose parents immigrated from the Madeira Islands, a Portuguese possession off the North Africa coast. Gonsalves began playing alongside the mill workers in Fall River, Mass., and emerged as one of the country's best players as a teenager with teams in Boston and Cambridge. At 21, Gonsalves was a key player for the U.S. in the first World Cup in Uruguay and by 1934 had performed in two World Cups and been offered contracts by top clubs in Brazil (Botafogo) and Italy (Lazio), as well as a chance to play for the New York Yankees as a first baseman and pitcher.

Black players of Caribbean descent began to emerge on top U.S. teams in the 1940s. Heron, a Jamaica-born forward, joined the Detroit Wolverines in 1946 and led the North American Soccer Football League with 15 goals in eight games. In 1951, a Celtic scout spotted Heron and the club brought him to Glasgow.

But if Heron broke a color line in the U.S., there does not appear to have been as much conscious resistance to the inclusion of blacks in soccer as in baseball or basketball. Gene Olaff, a U.S. Soccer Hall of Fame goalkeeper who retired after the 1953 season, said he does not even remember Heron. Olaff does recall Villanon, a forward who was among the leading scorers in New York-area leagues, as "one of the top players."

Heron's life does warrant at least a chapter in someone's book, though that would take some concentrated researching. Much of the available information on Heron comes from British sources, and there is nothing current, the trail ending with Heron becoming a referee from 1956-68, according to National Soccer Hall of Fame historian Colin Jose.

Heron served in the Royal Canadian Air Force in World War II, then joined the Detroit team in the startup NASFL. While Heron was playing in Chicago in 1949, he fathered Gil Scott Heron, who would be rais

By Frank Dell'Apa

Special to ESPN.com

If he were playing soccer today, Giles Heron might be preparing for Champions League games with Celtic FC. And, once his European career concluded, Heron would be recruited by the Chicago Fire to return to the city where his son was born and where his career was launched.

But when Heron became the first black player to perform for Celtic in 1951, there was no Champions League competition. Heron was accepted by Celtic supporters but, apparently, not the media. When Heron returned to the U.S., there was no demand he be included in World Cup preparations. As soccer's profile lowered, Heron also faded away.<DIV class=phinline>

<DIV style="WIDTH: 205px"><DIV class=photocred2>Matthew Lewis/Getty Images</DIV><DIV class=photosubtext>DaMarcus Beasley is part of a modern generation of black players making their mark in U.S. soccer.</DIV></DIV></DIV>

Heron, Haiti-born Joe Gaetjens and Cuban Pito Villanon were among the top scorers in U.S. soccer in the 1940s and '50s. There is almost no written material available regarding the integration of black players into soccer in the U.S. during this time, but there must have been other black players involved in the many semi-professional leagues throughout the country.

In the early years of soccer, administrators and players of direct Northern European descent dominated the game in most countries, including the U.S. By the 1920s, many U.S.-born players were advancing into the professional ranks, Italian and Portuguese names beginning to appear on top teams in the late '20s. An African player, Egyptian inside forward Tewfik Abdallah, starred in the American Soccer League from 1924-28. But the professional game in the U.S. essentially mirrored the British for decades and players of sub-Saharan origins were mostly excluded.

The first native-born superstar soccer player in the U.S. was Adelino "Billy" Gonsalves, whose parents immigrated from the Madeira Islands, a Portuguese possession off the North Africa coast. Gonsalves began playing alongside the mill workers in Fall River, Mass., and emerged as one of the country's best players as a teenager with teams in Boston and Cambridge. At 21, Gonsalves was a key player for the U.S. in the first World Cup in Uruguay and by 1934 had performed in two World Cups and been offered contracts by top clubs in Brazil (Botafogo) and Italy (Lazio), as well as a chance to play for the New York Yankees as a first baseman and pitcher.

Black players of Caribbean descent began to emerge on top U.S. teams in the 1940s. Heron, a Jamaica-born forward, joined the Detroit Wolverines in 1946 and led the North American Soccer Football League with 15 goals in eight games. In 1951, a Celtic scout spotted Heron and the club brought him to Glasgow.

But if Heron broke a color line in the U.S., there does not appear to have been as much conscious resistance to the inclusion of blacks in soccer as in baseball or basketball. Gene Olaff, a U.S. Soccer Hall of Fame goalkeeper who retired after the 1953 season, said he does not even remember Heron. Olaff does recall Villanon, a forward who was among the leading scorers in New York-area leagues, as "one of the top players."

Heron's life does warrant at least a chapter in someone's book, though that would take some concentrated researching. Much of the available information on Heron comes from British sources, and there is nothing current, the trail ending with Heron becoming a referee from 1956-68, according to National Soccer Hall of Fame historian Colin Jose.

Heron served in the Royal Canadian Air Force in World War II, then joined the Detroit team in the startup NASFL. While Heron was playing in Chicago in 1949, he fathered Gil Scott Heron, who would be rais

Comment